A good grip on pricing is a sign of a strong brand, and several behavioural studies offer insights into effective pricing strategies.

Warren Buffett is arguably the greatest stock picker of our lifetime. If you’d invested $100 in his investment company, Berkshire Hathaway, when it was founded in 1964, you would now have $2.2m. That certainly beats a cash ISA.

Luckily for those of us without his gifts, Buffett is open to sharing his thoughts about investing and business in general. His speech at Berkshire Hathaway’s AGM is such a draw that more than 40,000 people trek to Omaha, Nebraska each year to hear him. And one of the topics he returns to again and again in his speeches is pricing.

Buffet once said: “The single-most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by a tenth of a cent, then you’ve got a terrible business.”

Since pricing is so important, stop for a second and reflect on what happens at your company. Do you need to hold a metaphorical prayer session before raising prices? If so, help may be at hand.There are a range of behavioural science experiments that show us how best to communicate prices.

One theme from these studies is that people don’t weigh up prices in a fully considered manner; they are faced with too many daily decisions for them all to be evaluated in depth. Instead, people use quick rules of thumb to evaluate the priciness of a product. That’s relevant to us as these shortcuts are prone to biases; if we communicate in a way that aligns with these biases we’ll be working with human nature.

Let’s explore a couple of those opportunities.

Extremeness aversion

The first broad finding is that people tend to evaluate prices in a relative, rather than an absolute, manner. A product isn’t judged solely on its own merits but in contrast with a mental competitive set. If you can change that comparison set, then you can boost willingness to pay. One technique for doing that is to harness an idea called ‘extremeness aversion’.

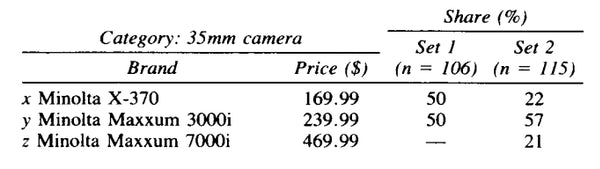

The earliest experiment into extremeness aversion was conducted in 1992 by Amos Tversky and Itamar Simonson from Stanford University. They offered 221 participants the choice of two cameras: the Minolta X-370, priced at $169, or the Minolta Maxxum 3000i at $239. The cameras proved equally popular: 50% chose each option.

The researchers then showed a second group three cameras: the original two plus a high-end Minolta Maxxum 7000i, priced at a rather punchy $469. The expensive camera didn’t prove that enticing – only a fifth opted for it. But, interestingly, the relative popularity of the other two cameras shifted. Now, more than twice as many people chose the $239 option as the $169 version. You can see the data from the original experiment in the table below.

The introduction of a high-end option led to the middle option becoming more popular. In this scenario, the $239 camera is reframed from being an extravagant purchase to a more palatable one – you’re saving $200-plus on the 7000i after all.

It’s easy to apply this finding. Say you’re selling two variants of your brand – a basic one and a higher-margin premium one. You can encourage sales of the premium line by introducing a super-premium version.

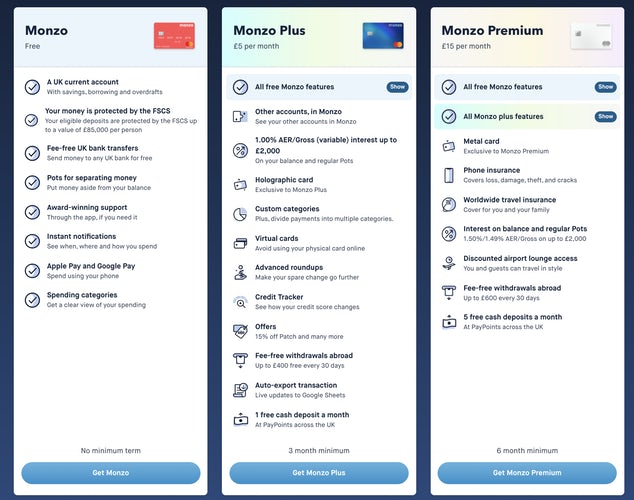

If you do, you’ll be in good company. Have a look at Monzo below. The Monzo Premium package has a value beyond its direct sales. It encourages people to upgrade from the Basic to Plus account.

The basic concept of price relativity can be applied more laterally too. One example comes from the now-defunct JJB Sports, which widely stocked Nike’s most expensive, super high-end football boots, despite rarely selling any. The store’s justification was that when they delisted these high-end boots it had a detrimental effect on its next most expensive pair. Shoppers felt uncomfortable buying the most expensive boots, as it felt wasteful. But they would happily buy the second most expensive pair as they could justify it as a relatively restrained purchase.

From basic to nuanced applications

Extremeness aversion is reasonably well-known. But there are plenty of other, equally powerful but lesser known, behavioural science principles. Let’s turn to one such idea: the ‘order effect’.

The insight around the order effect comes from Donald Lichtenstein at Colorado University. In 2012, his team ran an eight-week experiment in a craft beer bar in the US.

When drinkers arrived at the bar, they were given a menu of 13 beers. Sometimes the researchers handed out a menu with a $4 beer at the top and progressively more expensive beers below. On other occasions the drinks were listed in descending price order.

The psychologists found that, when the menu had a low-priced item at the top, the average price paid was $5.78. But, when the menu order was flipped, the average price rose by 24c to $6.02 – a statistically significant increase.

But why? Well, the authors argued that the first beer you spot has disproportionate importance in determining what’s a reasonable amount to pay. If you spy an expensive $10 drink first, it reframes a $6 beer as a $4 saving on that reference point. Whereas, if the first beer you spotted was a $5 beer – well, then, the $6 beer feels like an extravagance.

Again, this finding has practical implications. Think about Monzo and its three packages. According to the order effect, it should flip the presentation. Since people read left to right, Monzo should position the most expensive Premium package on the far left.

Temporal reframing

The order effect isn’t the only underused bias. One other that could be applied more regularly is temporal reframing.

Once again, let’s start with an experiment. In 2016, 500 participants were shown a car financing deal. Everyone saw the same image and basic details, but the way in which the price was displayed varied between participants. Some people saw the price conveyed as an annual amount, others a daily, weekly or monthly figure. On each occasion, the costs were the same if annualised. You can see the setup below.

Everyone was then questioned as to how good value they thought the offer was.

The results were clear: the longer the unit of time used, the less appealing the deal. This wasn’t a small effect. There was a five-fold variation in scores. Only 11% of people thought the car was a great deal in the annual variant. That jumped to 40% in the monthly condition, rose slightly in the weekly variant and peaked, at 51%, with the daily amount.

When calculating a deal’s desirability, consumers overemphasise the sum quoted and place too little weight on the time-frame. Think how striking this is. It’s as if consumers repeatedly estimate 7×4 to be smaller than 4×7.

You can apply this principle easily. Wherever possible, talk about your daily rather than monthly price. Or, if you’re selling multi-packs, don’t talk about the headline price; instead, emphasise the per-unit cost. That approach is being applied by Zoho, the online productivity company, in the ad below. £1 a day feels so much cheaper than £365 a year.

The great thing about these studies is that they don’t require multimillion-pound ad campaigns. They’re often small tweaks with outsized impacts. For example, with temporal reframing, you have to pick a unit of time to display your price. Why not choose the way that works to your advantage? It doesn’t cost anything extra.

In this article we’ve selected three studies, but there are literally hundreds of others you can use. Hopefully, if you apply one or two, that prayer meeting will become redundant.

This article was originally pubilshed in Marketing Week. written by our head of behavioural planning & strategy, Will Hanmer-Lloyd, and Richard Shotton.